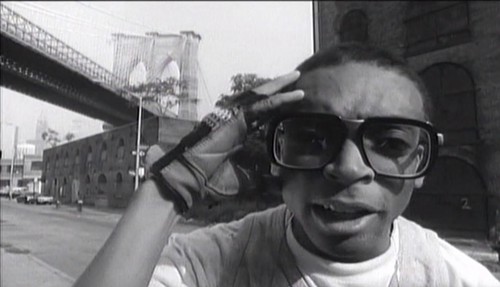

Talking to Spike Lee: “I’m Not Controversial”

Red Hook Summer, Spike Lee’s latest movie, is the most recent entry in what this sometimes great and always interesting director calls his “chronicles of Brooklyn,” which also includes She’s Gotta Have It, Do the Right Thing, Clockers, Crooklyn, and He Got Game. Elise Nakhnikian talked to Spike this week about his new movie, the old neighborhood, George Wallace, film school and more in his Fort Greene production office.

What they say about journalism, that it’s the first rough draft of history, could also be said of most your films. Plus, you’ve popped up as a sort of an expert witness on black history in other people’s films, like Hoop Dreams, When We Were Kings, and Brooklyn Boheme.

[Laughs] Yeah, I’m trying to cut that down. Can’t talk on every documentary. Can’t do it!

How much of that comes from having a conscious desire to correct the record because so much of black history has been pretty much swept under the rug, and how much is it just that these are the stories you are interested in?

I think artists reflect who they are, their culture. That’s what it is. I mean, Kurosawa, what’s he gonna do? He’s not gonna make a movie about Eskimos. What did Fellini do? Visconti? Satiyajit Ray? Artists tend to do stuff about what they know, who they are, how they grow up, their environment.

When you started developing Red Hook Summer, did you start by thinking, “I want to do something about gentrification in Brooklyn?” Or did you start with the characters, or what?

No, no, the issue of gentrification was not something that came right away. The initial kernel of the story James McBride and I wrote together was about this young kid [Flik] from suburban Atlanta being sent up north to spend the summer with his grandfather, who’s a Baptist preacher, and who’s someone he’s never met before. And then after that, all the other stuff came with it.

What interested you guys about that part of Brooklyn?

James grew up in Red Hook. And we both had kids who were Flik’s age, and we wanted to see young black kids in a movie. Who aren’t in gangs.

You were also born in Atlanta and came to Brooklyn as a boy—only I guess you were a little younger than Flik.

A lot younger.

How old were you?

Two years old.

You’re so identified with Brooklyn now. How would your life have been different if your parents hadn’t moved here?

I wouldn’t be a filmmaker. My mother was an art teacher, my father was a jazz musician. Where else were they going to be able to do what they did except in New York City? That impacted me as an artist.

Can you talk a little about growing up here?

We first moved here, we lived on 1480 Union Street in Crown Heights. We moved to 186 Warren Street between Henry and Clinton. I went to P.S. 29. We were one of the first black families to move into Cobble Hill. It was really strong Italian-American. Then my mother, who was a visionary, said let’s buy a brownstone. So 1968, we bought a brownstone on Washington Park, which faces Fort Greene Park, for $40,000. That was back when realtors wouldn’t even say Fort Greene. They would say “downtown.” [Laughs] So I witnessed firsthand the gentrification that took place in my neighborhood. We had the crystal ball in Do the Right Thing. John Savage’s character, he was the start. I’ve seen them all get gentrified: Lower East Side, Harlem, Williamsburg, Bushwick, Bed-Stuy.

You might also like