The 100 Most Influential People in Brooklyn Culture

It might have taken the rest of the world a while to notice, but Brooklyn has long been a hotbed of culture. Dating back to the early 19th century, Kings County has been a center for theater and music (the Brooklyn Academy of Music had its start with a performance of Mozart and Verdi in 1861; Mary Todd Lincoln came to a show the inaugural week); art (the Brooklyn Museum officially opened in 1895, but has roots dating back to 1823); literature (the borough’s book culture is legendary, from Walt Whitman to Djuna Barnes to today’s thriving lit culture); and film (the American Vitagraph Company made movies in Brooklyn starting in 1897).

But as glorious as Brooklyn’s cultural past is, we like to think that our cultural influence has never been stronger than it is today. Filmmakers, writers, musicians, painters, playwrights, actors… many of them still make their homes in Brooklyn and contribute to a cultural scene that is vibrant and innovative and—at its best—reminds us why we love to live here. Culture doesn’t happen in a vacuum, however, and behind every great institution and festival, bookstore and production company are the people who make it happen. This list is a celebration of those people, whose work guarantees that Brooklyn will never be just a punchline for a joke about artisanal cocktails or fancy pickles. And, look, we like fancy pickles as much as the next person, but culture is the foundation on which all this was built, so let’s celebrate it. Maybe with an artisanal cocktail? Why not.

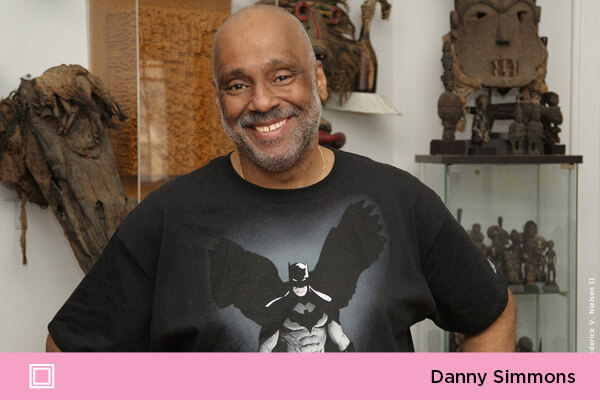

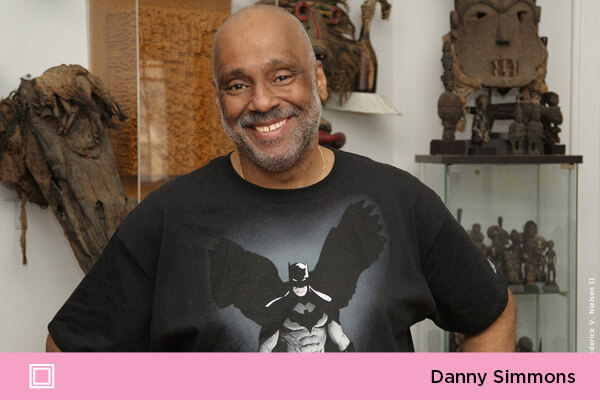

Photo by FVNielsenII

Danny Simmons

Philanthropist

The older brother of hip-hop impresario Russell Simmons and Reverend Run of Run D.M.C., Danny Simmons has kept his life and career focused squarely on the place he calls home. His Crown Heights home houses an impressive collection of African art; he opened a Brooklyn outpost of Rush Galleries, called Corridor, in Clinton Hill; he long served on the board of Brooklyn Museum, and currently sits on the board at BAM, Brooklyn Bridge Park and Long Island University Brooklyn, where he also studied.

Deborah Brown

Interview by Paul D’Agostino

The artist, local organizer and director of Storefront Ten Eyck has been radiating her creative energies in a number of ways that have responded to, benefitted and benefitted from the bubbling art community in Bushwick.

You’ve been a New York artist for many years, previously based in Manhattan. What encouraged you to make the shift to Brooklyn?

I came to Bushwick by accident one summer evening in 2006. I knew nothing about the neighborhood except for its infamous history and the events of July 13, 1977. At the time of my visit, the city was repaving Flushing Avenue, and it was ‘one way’ going OUT of Bushwick. With lots of kids playing in the open hydrants and the backdrop of tenements and vacant industrial buildings, it felt like a world apart. I landed at The Northeast Kingdom, which represented ‘fine dining’ in the neighborhood. I was intrigued by what I saw in my brief visit and set out to find a garage in the neighborhood that I could use as my studio. I looked at the building that Tandem occupies now and the building that Jules de Balincourt turned into Starr Space. Three weeks later I was the owner of a vacant factory on Stockholm Street. My attraction to the area was immediate and intuitive. I recognized that Bushwick had the potential to be a great artists’ area, and I wanted to be part of it.

Well, that has most certainly come to pass. What was Bushwick’s creative scene like when you first moved your studio there?

Artists were in the neighborhood, but there were many fewer of us than there are now, and we were less aware of each others’ locations and activities. Many storefronts were vacant and very few people were walking around at night. After a few months of walking the streets, I began to recognize the same cadre of people and say hello to them. The Wyckoff Starr coffee shop opened in September 2006 and this became a gathering spot for artists. There were few places to congregate—no coffee shops, bars or restaurants—so we frequented the same spots. In the absence of activity on the street, I looked to the internet to discover who else was out there. Eventually, Starr Space, English Kills, Ad Hoc, Lumenhouse, Pocket Utopia and Factory Fresh opened. Spaces like Norte Maar, Privateer, Centotto and Little Town in the Woods began showing artwork in lofts and apartments. Jeremy Sapienza started Bushwick BK, a blog that helped identify who was coming to Bushwick and what they were doing. Bushwick Daily followed in its wake. The absence of many of these spaces today speaks to the fragility of artist-created neighborhoods. Even as we have flourished and expanded, some of our early members are gone. In 2007, the current organizers of Bushwick Open Studios took over from its original founders and re-launched the festival. Some dozen people met in Laura Braslow’s loft on Melrose Street that spring to plan BOS 2007. It was exhilarating. We felt like we were mapping the artistic energy of the neighborhood. It was the beginning of what we now recognize as the creative community in Bushwick working together.

Those meetings at Laura Braslow’s really were a lot of fun. When you expanded your arts engagements in Bushwick to running a gallery as well, what were some of the biggest challenges? How has your programming changed now that you’ve moved your gallery into a much larger space?

Being an artist and running a gallery makes for a busy life, but there is a synergy between the two activities. All artists do studio visits, and artists often know who is doing exciting work before it is shown in commercial galleries. For me, selecting work for shows is a pleasure and an aspect of my creativity as an artist. As I have worked as a curator, my eye has grown sharper—both about others’ work and about my own. As to the logistics of running a space, I had to learn many things: how to compose emails via constant contact, hang shows, maintain a mailing list, direct artwork in and out of the space, design announcement cards and communicate with the press, collectors and artists. The original Storefront was a great place to learn the craft of running a gallery because it was a small space. But after 4 years, I felt that I had said all I wanted to say there. Moving to a bigger space (from 400 square feet to 7000) has meant an increased commitment of my energy, time and organizational discipline. I can now show much bigger work and host more ambitious, guest-curated shows, but otherwise it’s a continuation of my program. The biggest challenge is the physical work of running the building. I do this myself to keep expenses down, and it’s a big job!

In which ‘big’ is quite an understatement! Cite a few of the most dramatic changes you’ve witnessed in Bushwick over the years. What’s been lost, in your opinion? And gained?

The retail landscape has exploded in the last year or so. Things plodded along for years without much outward change and suddenly everything is out in the open: new bars, restaurants, vintage clothing stores, gallery buildings, pet stores, re-made supermarkets, shiny condos. You take for granted this kind of development in Manhattan and in other parts of Brooklyn, but these were rare sites even 4 years ago in Bushwick. Now developers are at work on every block. The New York Times has an ongoing love affair with our neighborhood, gushing over locavore food, art or hipster antics on a regular basis. There are many more members of the ‘new’ community walking around, deeper into the neighborhood, not just at the Morgan stop. It’s staggering how quickly the changes have come. No wonder members of Community Board #4, who have lived in Bushwick their whole lives, have begun to express alarm and anxiety at the speed with which they seem to be ‘losing their community.’ One group’s gain has been another’s loss, it seems. The problems of displacement and resentment over gentrification are not easy to solve.

You’ve been presiding over meetings of Bushwick gallerists for many years and have come to know a number of local politicians. Can you describe some of those involvements?

In 2012 I organized the galleries by forming a group open to all who run an art space in Bushwick and Ridgewood. I thought it was time for us to put faces to names and to become more aware of each other’s programs. Visitors to the neighborhood were arriving in increasing numbers with the intention of visiting the galleries but were unable to find a central place on the internet to access our information. I bought the domain name, bushwickgalleries.com, knowing that one day we would need it. Henry Chung generously created a joint website where we can upload our websites, exhibitions, locations and openings. Now the public can access our information in one place, which helps everyone gain more audience. Our gallery meetings have provided an opportunity for us to organize joint gallery walks in conjunction with the art fairs and to work in sub-groups on projects that interest us. All are welcome and the exchange of information is productive and democratic. The local politicians are interested in the art community. Former Council Member Diana Reyna, former Assemblyman Vito Lopez and former Borough President Marty Markowitz all made overtures to the art community. Congresswoman Nydia Velasquez and newly-elected Council Member Antonio Reynoso want to form alliances with the ‘new community.’ I think it’s important to recognize that these individuals owe their election primarily to community residents who have been in Bushwick for decades. I sense that the older community and its elected officials remain wary of the artists, unsure of their permanence in, and allegiance to, the neighborhood. Any thoughts on the future of art spaces and events in Bushwick? Or in Brooklyn in general? Bushwick is experiencing a bit of a Golden Age right now where anything seems possible for the creative community. It’s our moment, and I am enjoying it, but it’s always bittersweet. Nothing lasts forever.

Rebecca Fitting and Jessica Stockton Bagnulo of Greenlight Books

Co-owners and founders of Fort Greene’s beloved, Fitting and Stockton Bagnulo have created a space for avowed lit lovers and newbie readers (they’re out there!) alike. And beyond just running what happens to be one of the most pleasant bookstores in the borough (and this is a borough full of pleasant bookstores) Fitting and Stockton Bagnulo run an excellent reading series at Greenlight, with an exciting list of visiting authors stopping by to read and chat, including, most recently, Gary Shteyngart and Rosie Perez.

So you’re the co-founders of Greenlight Bookstore (one of our favorite places in all of Brooklyn) and also responsible for hosting some of the best lit events in town… you do it all! What would you say are some of the most important things going on in Brooklyn’s literary culture today?

Stockton Bagnulo: Wow, starting off with a hard one! Really there has always been a vibrant creative scene in Brooklyn — perhaps one of the most important things that’s happening is that the attention of Manhattan — in the sense of the big publishing houses, major cultural organizations, etc. — is now turning toward Brooklyn as an established center of literary culture. That means Brooklyn is thought of as a distinctly separate market for major author tours (as opposed to the idea that “New York” is a single market), and that longstanding literary organizations are looking to establish a presence in Brooklyn as well as Manhattan. And this applies nationwide and worldwide too — we love it when booksellers or authors or publishers from elsewhere arrive in our store and tell us that they’re doing a “Brooklyn literary tour!” The literary culture is well-established, and now it’s becoming… well, the establishment.

Fitting: Thank you for the kind words! It feels like we are in the heart of bohemia.

There’s a great confluence of artists, writers, patrons and readers all meshing together in this borough. You’ve got authors, publishers, agents and editors living here, co-mingling with our everyday lives. Some of the most exciting authors and writers are right in our own back yard and the person who wrote your new favorite book might be standing in line behind you at the supermarket. I think that’s pretty special. But also, and I think this is really important – our booksellers here at Greenlight have opened my eyes recently to how special Brooklyn’s small presses and micro presses are, and even though some have been around for years now, it feels like they are bubbling up in a significant way. I think over the past few years Brooklyn’s been experiencing a ‘moment’ of major literary culture and now this second wave is coming in of the small and micro presses getting the attention they’ve long deserved. It’s pretty wonderful to watch. Also, not for nothing, but Brooklyn hosts one of the largest annual book festivals nationwide.

There’s always a lot of chatter about the Brooklyn lit scene, but what does it mean to you? (If anything.)

Stockton Bagnulo: Also hard! At best, I think Brooklyn can be an environment that’s conducive to a neighborly cooperation — we certainly see that with our fellow Brooklyn indie bookstores, and we hear it from authors who appreciate the community of fellow creators they can work and hobnob with. The neighborhood scale of the borough contributes to a slightly more relaxed atmosphere than that of Manhattan, and brownstone stoop culture translates metaphorically to people getting to know their neighbors, even if they’re very different from each other. At worst, it’s just branding, right? We groan a bit when we see authors we respect who live elsewhere setting their novels in Brooklyn — it’s not the only literary place in the world, and we’d rather read a diversity of voices and setting and perspectives than have Brooklyn become a black hole that sucks in everyone doing any kind of literary work.

Fitting: I’ve been thinking about this question for days now, trying to figure out what to say! There’s a TON of chatter about the Brooklyn lit scene. So much that some days I feel a little bit numbed by it, but then I think back to when I was in my teens growing up outside New York City The exciting destination was the East Village. Astor Place. I’d cut school and take the train in, hang out there for the day, then walk over and kick around at The Strand. The books I read were set downtown. Brooklyn today is what gritty downtown Manhattan was for me when I was coming up and discovering art, literature and culture. It’s where the books people want to read are set, it’s where exciting authors and artists live, and it’s the ultimate destination for creative aspirers. Is aspirers a word? It should be if it’s not. It’s where young people want to be, or are excited by. That’s not to say that the Brooklyn ‘lit scene’ is all comprised of young folks, but what I find so interesting right now about Brooklyn is…in an era where people and data tell us that young people aren’t reading, I feel like it’s the young folks who are sustaining the momentum of Brooklyn being described as a ‘scene’.

Would you say that Brooklyn has a cultural scene that is distinct from that of the rest of New York?

Stockton Bagnulo: In some ways Brooklyn’s cultural scene is coming to define the rest of New York! But I think you could answer this question many ways depending on how you look at it. On some level every block, every room and writing desk has a distinct literary culture, and certainly different neighborhoods are defined by their own residents, geography, bookstores and other cultural institutions. But at the same time New York is still New York, in the eyes of much of the world, and there’s certainly a lot of overlap and mixing between the boroughs, especially Manhattan and Brooklyn.

Fitting: Brooklyn nurtures its creative culture in such a lovely way. It feels big enough to be a city yet small enough to be a community. I am constantly hearing authors talk about other authors in supportive ways. Everyone shows up for each other’s readings (and buys each other’s books). But it’s more than that – they make sure that it’s not a closed community. It’s open and accessible in a way that feels very special.

Who are some of the writers that you’re most excited about right now? Stockton Bagnulo: Ooh a fun one. I am crazy about Helen Oyeyemi — her new book Boy, Snow, Bird is haunting me, and it’s exciting that she’s written several masterpieces and is still so young. David Mitchell is probably my all-time favorite fiction writer, and he has a new book coming this fall so that’s exciting. And I am loving some young writers of essays and creative nonfiction that encompass politics, culture, nature, life — Amy Leach (Things That Are) and Leslie Jamison (The Empathy Exams) are new discoveries for me.

Fitting: Phil Klay’s debut story collection Redeployment is one of the best books out there right now (possibly this entire year). I think it deserves to win the National Book Award, it’s that good. Another writer I’m super excited about right now is Matthew Thomas. His debut novel doesn’t come out until September, later this year, but I’m reading an early copy now and it is wonderful. It’s like John Irving or Chad Harbach – a great storytelling novel where it’s all about the characters, set in Queens.

What are some of the defining cultural moments of your life? (Movies, books, TV shows, albums…certainly don’t need to be related to Brooklyn.)

Stockton Bagnulo: Hmm… David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas… Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek… and don’t laugh, the 1980s Australian Western The Man From Snowy River. It’s about leaving home to live and work in the big city so you can figure out how to go home again… probably part of the reason I came to New York.

Fitting: I don’t know that I have specific movies, books, shows etc that define me but so much of my experience is tied to geography – places and the experiences I have in them affect me a lot. So, formative moments and experiences have happened in Grand Central Terminal, Memphis TN, Berkeley CA, Salem MA, Oxford MS and Baltimore MD. There of course have been conversations in dive bars that were seminal, books read on front stoops that were mind-opening, concerts that changed my perspective on crowds, and cross country road trips that made me talk to myself waaaay too much but that also cleared my head. I know that probably doesn’t really answer your question but…it’s the best I’ve got at this time!

Where do you see Brooklyn headed in the coming years? Will it still be a home to writers and artists, despite the high cost of living and lack of available real estate?

Stockton Bagnulo: Well, you’ve identified the issues, sure enough. This is totally a copout, but I think it’s impossible to predict the future, except that it will be different from what we imagined. Cultural hotspots are probably bound to move around. But Manhattan has the same problems Brooklyn is starting to have with affordability, and it’s still one of the cultural centers of the world. It might not be the cutting-edge fringe, but it’s where everyone wants to come to have their great success, their moment of cultural glory. So perhaps that’s what’s in store for Brooklyn.

Fitting: I think Brooklyn will always be a home to writers and artists but I do worry that as time goes by and cost of living goes up, it’ll be harder for new young talent to establish themselves here. So maybe what will happen is that the young new artists and writers who set themselves up here now will establish themselves and stay, but the next generation of young artists and writers will find another place to colonize, much the way it’s happened with the West Village (or, even Woodstock, NY if you think about it). There’s a cycle to how these things go – it’s very human.

Ric Leichtung

Independent BookerThe cavernous, dingy, magical DIY music space 285 Kent made its booker Ric Leichtung a sort of neighborhood folk hero among members of certain scene, as the guy behind the scenes of multiple golden moments’ of their youth. But the venue’s end was hardly the end of Leichtung’s story. He continues booking and promoting shows in Brooklyn, at Baby’s All Right and elsewhere, and he continues to champion the weird bands he loves as a founding editor of the music blog, Ad Hoc, in his spare moments. We talked to Ric about the present and future shape of Brooklyn’s music scene.

What’s the best thing about the Brooklyn music community in 2014? Right now, more than ever before, there’s an outrageous amount of people who care about noise music and are receptive to really weird shit that wouldn’t be as appreciated to this degree in any other time than right now. The concept of what’s accessible and what isn’t is being challenged and blurred every day, to the point where I wouldn’t be surprised if Jandek died decades from now (god forbid), and Billboard ended up writing a really nice eulogy for him (if they’re still a thing…).

To what degree do you think the physical, external realities of living in Brooklyn (expense, shifting neighborhoods, changing venue landscape, practice space availability, etc.) change the actual sound of the music produced here? Do you even think specific living circumstances directly produce specific sounds?

It’s no secret that Brooklyn is expensive. Most of my friends are on a steady diet of rice and beans or $5 Hot-N-Readys from Little Caesar’s, so you better believe they’re not spending much money on pricey gear that makes things sound nice. A lot of the music coming out of this city sounds like shit because people are living like shit. It should come to no surprise to anyone that the sound of Brooklyn has gotten darker, grittier, and more abrasive over time. The living conditions are terrible to the point of being a total joke, and so are most people who can afford it.

What’s the single thing that doesn’t now exist here that would help local music thrive the most?

Free burritos?

Which Brooklyn neighborhood most needs a DIY space that doesn’t yet have a viable one?

Even though Bushwick is overrun by all these small DIY venues, none of them are really amazing and there’s a high demand for a place that can deliver to the neighborhood, which is incredibly saturated with young people wanting to get drunk and do things. The issue is that most of the venues in Bushwick don’t have the capabilities to make super crazy amazing bookings pop off. You need a capacity larger than 200 people. You need someone running it who’s not a pretentious idiot and won’t jerk bands around by not delivering on guarantees. You need key in-house tech stuff that big bands need, like subs, or decent monitors, or backline. A Bushwick venue could conceivably have all those things, but it’d take a crazy budget to make it happen. Investors get in touch, LOL.

Is a 100 percent legal DIY music scene in Brooklyn an attainable goal in the next five years? A desirable one?

I don’t think so. With the kind of music that interests me, which is generally on the obscure, needlessly esoteric side, I don’t think so. To do things legit you need to have money coming in through the door. People behind legitimate venues are also responsible for paying the rent. I can tell you from experience that noise music doesn’t pay the bills.

As a booker, what traits make a local band catch your eye/ear?

There’s so much crap out there that sounds the same and a lot of the time none of it is worth a damn. I look for things that sound wildly different—if you don’t have that then you don’t have anything.

Are there any style trends you see forming here right now that you think will be a big deal in the next six months/a year?

I think a lot of hardcore kids are broadening their pallets and flirting with dance music and noisy techno because it goes so well with industrial. There’s a lot of cross-pollination happening between the two scenes. I’m predicting that this type of stuff will totally take over at least a quarter of PS1 Warm Up’s bookings this summer.

Photo by Christian Torres

Ryan Schreiber

Founder, Pitchfork

There’s no denying that Pitchfork, the online music publication founded by Minnesota teenager Ryan Schreiber in 1995, became the most influential of its time. There isn’t a better way for an unknown act to get known than receiving a high-decimal rave from its critics. Now based in Brooklyn, Pitchfork’s reach has grown to incorporate a video network, yearly music festivals in Chicago and Paris, an iPhone app, a film criticism blog, and even a ballsy attempt to restore music journalism in print with its glossy quarterly, The Pitchfork Review. We asked Schreiber about his site, and being a music fan in his adopted home.

What has Pitchfork gained in the years since it moved its editorial offices to Brooklyn?

Pitchfork has grown up a lot since relocating its editorial team to New York. That’s not necessarily a result of being here, but there’s a broader range of talent to draw from than in many other cities, and it’s allowed us to better foster young writers and collaborate with established ones. There’s also the sense that everyone here is in constant competition, which keeps us driven and thinking ahead.

Do you see Pitchfork’s role as purely reflecting the music scene going on around you, or do you aspire to actively shape the direction its heading? Can shaping/steering trends even be avoided given the site’s influence?

We generally gravitate towards artists who are pushing music in new directions or thinking differently about existing forms, because they’re the ones who tend to shape where music is headed. I see recognizing these artists as our responsibility, and we look for that kind of perceptiveness and forward-leaning taste in our contributors. Ultimately, though, music trends are shaped by artists and the technology they work with, and our job is to note where the most exciting stuff is happening and place it in context.

How do you think the idea of a “Brooklyn band” has changed in the decade since the local music scene really exploded in the early 00s?

I’m not sure that there’s been an explosion, it’s more that the geography changed. A decade ago, bands like the Strokes and Yeah Yeah Yeahs still came out of Manhattan. Once the city became too expensive, the scene migrated, and the industry eventually followed. Now many of the same stigmas are attached to Brooklyn bands as were New York bands. The rents really were still cheap enough a decade ago that a new community sprung up here, and gave rise to the DIY/punk scene. But now that’s splintering— some of the DIY stuff is receding to the underground, and some of it is mutating into dance culture. And all of those artist communities are moving further east, because the rents in Williamsburg, Greenpoint, and Park Slope are getting close to Manhattan rates. As far as the rest of the country is concerned, Mumford & Sons might as well have been a Brooklyn band. You still see these funny, out-of-town banjo buskers on Bedford Avenue, and they’ve got the whole package— the raccoon-skin caps and suspenders, another kid on a fiddle, maybe some yodeling. Oddly, not many Brooklyn bands actually subscribed to that style, but I guess enough of them were named after animals that it stuck.

Do you think young musicians are better served by the sort of intense spotlight that living and playing in Brooklyn brings, or would some percentage of the musicians who flock here be better off with some time alone, outside of a media Mecca, to establish a voice?

There are enough bands here that most of them can exist outside the spotlight if they want to. I’ve also seen loads of bands play horribly sloppy sets early on and gradually became more polished. If anything, the media could stand some time outside of the city because it does get a bit myopic at times. It helps to maintain geographical diversity among contributors, which not all New York-based publications actually do.

What thing do you think the Brooklyn music community doesn’t have right now that it most needs?

A good venue that’s not specifically dance-oriented. A few good spots have opened up since some of the recent mainstays shut down, but the ambiance isn’t always flexible enough to accommodate different kinds of artists. I’m actually considering investing in a new space that some friends are planning to open, because their concept is brilliant— it’s like nothing I’ve seen before. While my involvement wouldn’t extend beyond that, it’d be really exciting to help bring it to life.

What’s your favorite thing about being a music fan living in Brooklyn right now?

I appreciate that there are limitless options to see any kind of music in any type of setting. Lately, I’ve been checking out rock stuff earlier in the night and then wind up later at places like Output, Cameo, and Bossa Nova Civic Club, which specialize in house and techno, or some of the weirder underground spots in Bushwick. The PS1 Warmup parties in the summer are amazing, too.

What’s your favorite thing about being a music fan living in Brooklyn right now?

My favorites at the moment are Anthony Naples, Mas Ysa, and Torn Hawk. All-time? It’s too hard to choose just one. TV on the Radio, Grizzly Bear, and ODB.

Jenn Northington

Events Director of Word

There aren’t a lot of bookstores where you could count on say, events focusing on Rousseau and Riot Grrl happening on the same day, and even fewer with a space as cozy and lovely as the one at Word. Kudos to booker Jenn Northington for running the show at a place that truly deserves every bit of adulation that come its way.

Benjamin Samuel and Halimah Marcus

of Electric Literature

As independent and corporate-owned bookstores alike shutter around us, Electric Lit editors Samuel and Marcus have found a way to reinvigorate our love of literature by marrying the written word with the global reach and appeal of the Internet, simultaneously becoming tastemakers and curators in an era of literary bombardment.

Andrew Kalish, Director of Cultural Development at Downtown Brooklyn Partnership

Kalish was born and raised in Manhattan, then grew up to work at one of the preeminent cultural institutions in New York City: Lincoln Center. However, after moving to Brooklyn Heights not long ago, it made perfect sense for Kalish (an avid Citi Bike user) to start working closer to home. Well, we imagine there are several other reasons Kalish took a position as the Director of Cultural Development at the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership (including his unreserved enthusiasm for everything new happening in the Brooklyn cultural scene), but a short commute is not the worst reason in the world.

So tell me a little bit about what you do? You have a big, long title, but what does it all mean?

My job is actually pretty straight forward. Be a tireless advocate for the 50+ cultural groups in Downtown Brooklyn, and help facilitate an environment, by working with them, local business, elected officials and the community, where they can thrive and do their best work. All the while ensuring that Downtown Brooklyn remains a global cultural destination.

You were at Lincoln Center before (a New York cultural institution if there ever was one!), but what brought you to Brooklyn? And how do you like it here?

I live in in Brooklyn and the opportunity to be part of this community’s renaissance is simply an offer I couldn’t refuse. Couple that with phenomenal colleagues at the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership and perhaps the most dynamic cultural groups in the City, how could you not want that job?

There’s always a lot of chatter about the Brooklyn cultural scene, but what does it mean to you?

There could be an entire book written about “the chatter” of the Brooklyn cultural scene, and I will say this, after sitting down with most of the cultural groups in Downtown Brooklyn, I have yet to encounter one monocle…but in all seriousness, cultural in Brooklyn is not just a thread in the fabric of the community, it’s the foundation of the community. There is no better example of this than Downtown Brooklyn. Where else could you have Issue Project Room literally sharing a wall with the New York Transit Museum that is a block away from the Actor’s Fund where Brooklyn Ballet is based? And that doesn’t even scratch the surface. There are over 50 cultural groups here and the range of their offerings and quality of their work is breathtaking.

Would you say that Brooklyn has a cultural scene that is distinct from that of the rest of New York?

Every neighborhood has its own distinct cultural identity. However, there’s a certain pride to being in Brooklyn that I think is unique. These groups wear the Brooklyn label proudly and prominently and there is shared sense of responsibility to the community and to each other. This extends to collaboration, take The Brooklyn Historical Society’s partnership with Weeksville Heritage Center and Irondale Ensemble Project for “In Pursuit of Freedom,” an incredible production that spans Brooklyn Heights, Downtown Brooklyn, Crown Heights and Ft. Green. The Downtown Brooklyn Arts Alliance is another. These partnerships weren’t mandated, they grew organically out of a common desire to better serve the community and that’s amazing.

What are some of the defining cultural moments of your life? (Movies, books, TV shows, albums…certainly don’t need to be related to Brooklyn.)

I was fortunate that my parents didn’t believe that Art and Culture were optional and took complete advantage of living in New York City and all it has to offer. But if I were to name a few it would be seeing The Fantasticks when I was seven, spending countless hours exploring The Met, more often than not ending at the Temple of Dendur, and going to actual shows at CBGB’s and The Wetlands. More recently my work at Lincoln Center with its Poet Linc program was eye opening as I witnessed firsthand how the arts can make meaningful change in the lives of young people. Finally, participating in Go Brooklyn Art, put together by the Brooklyn Museum, which revealed the vastness of the borough’s cultural ecosystem and gave a platform to artists that would have a difficult time reaching an audience of that size.

“Where do you see Brooklyn headed in the coming years? Will it still be a home to writers and artists, despite the high cost of living and lack of available real estate?

Brooklyn’s future is only going to get brighter and I do believe that it will be a home to artists and writers for generations to come. Yes space is at a premium but at the same time you want new people to come to a neighborhood, you want investment in the community’s future and it comes down to balance. Brooklyn needs to stay Brooklyn, and based on everything I’ve seen that will be the case. There’s a great example of this right now in the Brooklyn Cultural District. All of the new buildings have large affordable housing components and two have over 40 percent of their units reserved for that purpose, that’s a tremendous commitment to keeping Brooklyn affordable. BAM is expanding, Theater for a New Audience had a hugely successful first season in its new home, EyeBeam is moving in from Chelsea! Incredible things are happening here and it’s only going to get better.

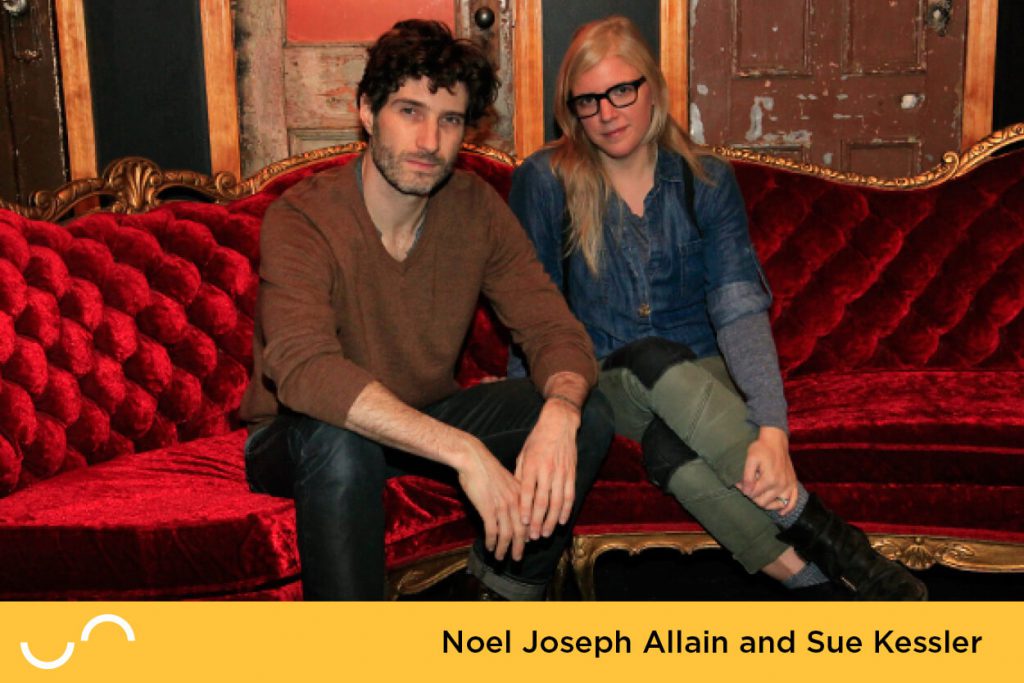

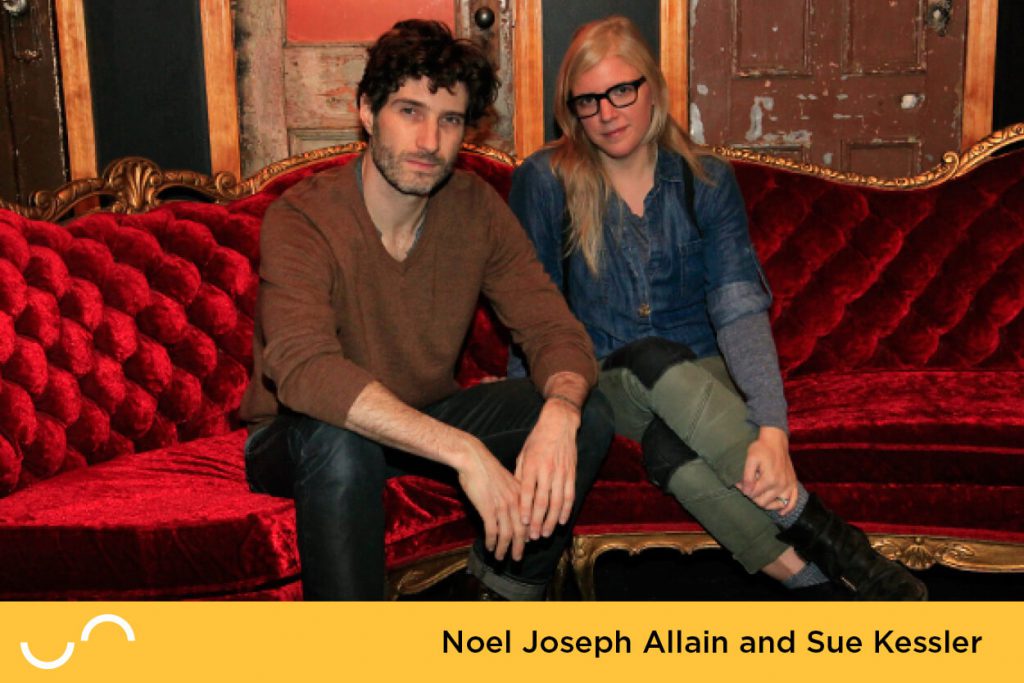

Noel Joseph Allain and Sue Kessler

Founders, The Bushwick Starr

Executive Director Kessler and Artistic Director Allain founded this theater (named for the street it sits on) in 2001 as a developmental space. In 2004, they built it out as a black-box venue, and in 2007 started renting it out to other troupes, quickly becoming one of the leading spaces in the borough for ambitious and cutting-edge theater programming.

Do you think about the unique character of “a Brooklyn audience” when deciding what to put on at the Starr?

Kessler: Absolutely! Brooklyn is leading the charge right now because of its uniqueness, so we always think about putting up work that will speak to our borough’s diverse tastes and artistic needs. Brooklyn both upholds the authenticity of our city’s history and cultures, and represents the future of NYC. It’s the new/old frontier, so it’s a very exciting place to be presenting work.

How do you feel about the cultural scene in Bushwick right now?

Allain: There are several. Gentrification is certainly infringing on many of them. To put a positive spin on it, you could say the area is even more diverse than it used to be, but at a certain point it becomes an economic issue and the money starts to drive out the culture. I’ve always been in love with the mix of grassroots arts orgs and artist studios alongside Bushwick’s Latino/Hispanic culture and community. There are all the tensions, collaborations, surprise relationships, and broadening of horizons that describe the New York I love. I’m just afraid the development is going to demolish it.

What about the general theater scene in Brooklyn?

Kessler: Brooklyn’s theater scene is growing bombastically every day, and that growth still feels intrepid, experimental, and of-the-people. I think there’s a natural instinct for Brooklyn theaters to reflect the distinctive cultures surrounding them, so community feels more tied to the work.

What do you think has been the best and/or most influential/farthest reaching thing you’ve put on since you started? Does anything besides box office signify success?

Allain: YES. Don’t get me wrong. Box-office success is very important and generally means people are responding to what you’re putting out there. But we’re programming artists in all stages of their careers and often helping introduce them to their audience. The Debate Society’s Blood Play was certainly the most successful and far-reaching piece we’ve presented, but those guys were poised to make that leap. If we can help an artist take an earlier step forward, that’s also a huge success. And, of course, help them make a piece they’re extremely proud of.

Which show(s) haven’t connected with audiences as well as you would’ve hoped? What did you learn from them?

Allain: I’m happy to say we’ve never had a huge disaster. I curate artists whose work I feel actively connects with the audience. Not everything is for everyone and that’s how it should be, but so far nothing has felt like a particular failure. Early on we learned a lot about how to present artists in different stages of development. When you open a show, the length of the run, how you market it… these factors all influence how it reaches people, and we’re always learning how to refine that process.

Which Brooklyn artists and cultural institutions are influencing you the most right now?

Kessler: BAM and St. Ann’s Warehouse are Brooklyn institutions I’ve always looked up to, both in terms of their impressive programming but also in the way they’ve navigated battles lost and won with the city in order to accomplish their goals. I also think the new BRIC House is a great model for community and art integration. But the newer spaces like Invisible Dog and JACK are often the most inspiring because they bring fresh energy and outlooks to the scene.

Allain: We’re about to present theater artist Daniel Fish at the end of March, and his work has been a big influence on me. It’s incredibly powerful because it’s so considered. He’s working with Andrew Dinwiddie who along with Caleb Hammons and Jeff Larson produce the Catch! Performance Series, which early on was an amazing way for me to see new artist’s work. They helped broaden my horizons.

Scott Adkins and Erin Courtney

Cofounders, the Brooklyn Writers Space

An Obie award-winning playwright, Courtney was a member of the prestigious, now-defunct theater cooperative 13P and has had her work performed at the Soho Rep and the Flea. A decade after getting her MFA at Brooklyn College, she’s now a lecturer there. She’s also the cofounder of the Brooklyn Writers Space with her husband, Adkins, who also curates its reading series at BookCourt and is the main force behind Sock Monkey Press.

Which neighborhood do you two live in? Is there a cultural community there?

We’ve lived in Park Slope for 14 years, and there is a great cultural community here: mostly writers of all genres but also actors, theater directors, designers, filmmakers and a multitude of other creative professionals. In our building alone, we have four playwrights, an actor and a theater director. We feel so lucky to be living next-door to so many creative people, many of whom are facing the same creative challenges. There are great visual artists and curators in Park Slope too. Ethan Crenson and Amanda Alic, are both artists and they are the mad geniuses behind Fuse Works, which is a multiples project. There are all these gathering places for artists, writers and musicians in Park Slope too: Community Bookstore, the Old Stone House, BAX, Barbes, 826NYC, the Rock Shop, Brooklyn Colony, powerHouse on 8th, Mission Dolores, Union Hall and many great watering holes. A lot of the local places for artists to gather have sprouted up in the last 10 years, including the Brooklyn Writers Space, which we opened because we didn’t want to travel to Manhattan to be part of a shared writing space.

What are your thoughts about the literary scene in Brooklyn right now?

The scene is vibrant. We currently have 250+ writer members at our Writers Spaces, but we’ve served 1,000+ writers in the past 10 years. I’m always amazed at the diverse genres that writers work in at the space. When we first started the space, a member, Rachel Stark, suggested we start a monthly reading series, so we did. Every month we have four writer members read their work at BookCourt on Court Street. BookCourt is an indie bookstore, weathering the storm that’s hitting brick-and-mortar book stores. They have a wonderful space for readings and events that they make available to the writers in our community. Sackett Street Writers Workshop is in it’s 10th year of providing high level writing workshops to new, emerging, and established writers in Brooklyn. If you are every in search of a hot reading, check the BookCourt calendar—you’ll inevitably find an author-you-know reading. Then there’s the Brooklyn Book Festival held every fall, which is now one of the largest in the country. Brooklyn is home to many cutting edge publishers including Tin House (a literary journal and publisher of individuals), Ugly Duckling Presse (publisher of books that are beautiful and poetic; they put out up to 35 titles annually, and you can get a subscription for $250, which is an insanely good deal), One Story (the ingenious magazine publishing a single story a time), and so many reading series like Stone House Reading Series hosted by Louise Crawford, Rabbit Tales Reading & Art Salon Series at the Rabbithole in DUMBO, and many indie book stores (Greenlight, Unnameable Books, powerHouse on 8th, etc.). I think it’s safe to say we’re in the spring time of the Brooklyn literary scene, and this scene spans the borough. We have met so many outstanding writers through the Brooklyn Writers Space that were yet to be published. This seemed criminal to us, so we rebooted our small press, Sock Monkey, in order to publish writers of all genres that are making exciting work. Our latest book is SuperLoop, a book of poems by Nicole Callihan, and we’re already on the second printing. Writers need venues in which to share their work.

Erin, what about the theater scene?

Brooklyn is a far better place to see theater now that we have the Bushwick Starr and Jack. Both of those venues are curating some of the most exciting and avant-garde work. Brave New World is also a great Brooklyn theater company that presents site-specific work of classics and with their new artistic director, Shannon Sindelar, they’re starting to produce new plays. The Brooklyn Arts Exchange has a performing artist residency program and is a great venue to see works in progress. The Brooklyn Writers Space joined with Brooklyn Arts Exchange and Gabe Miner to produce the annual Folk Play Project. This project is a festival of plays written and produced over a 24-hour period. The plays are inspired by a folk song assigned to each writer. BAX provides space and human resources, Brooklyn Writers Space provides space for the writers, and Gabe Miner brings the band. We have about 50 participants each year and Scott prepares three meals for them for the day of rehearsing and performing. I also have to give a shout out to the Chocolate Factory, which is in Queens, but so close to the Brooklyn border! I love every show I have ever seen there. I am excited about the new smaller theater at BAM and looking forward to what they program.

What kind of cultural influence can a Writer’s Space have?

Aside from providing a 24/7, quiet, professional destination to foster the literary success of all types of writers, early on we started the Brooklyn Writers Space Reading series. This series is unique in that we do not overly curate. Any writer member, current or former, has an opportunity to read in the series; we do not edit. The idea is to get the work out there, provide an arbitrary deadline, and to introduce the writer to a broader audience. We have four readers a month, each of whom bring 10 or more people to the event. The exposure is extremely beneficial to their processes but also gives locals access to work they might not normally see. We have also rebooted our indie press, Sock Monkey Press, to provide a platform for one or two writers a year to have their work published. Primarily we focus on experimental work, poetry, and performance texts; however, we keep our lines open. The Writers Space is home to a formidable talent base, after seeing members work year after year but not seeing it published, it became clear we could do something to help with Sock Monkey Press.

What kind of role do you think Brooklyn College plays in the borough’s cultural scene?

The creative writing MFA program at Brooklyn College is one of the best in the country. The undergraduate writing program is growing, and the theater department is producing great work. Mac Wellman took over the playwriting program in 2000. Over the last 14 years he has taught some of the most influential American playwrights, including Annie Baker, Thomas Bradshaw, Young Jean Lee, Sibyl Kempson, and Tina Satter. Our alumni are creating their own theater companies and touring the world with their shows. They’re also curating theater series like Little Theater at Dixon Place and starting their own presses like 53rd State Press. In an interview, Tina Satter said that she kept seeing amazing work and every bio said Brooklyn College and that’s how she decided to apply to the program. I have been teaching there for the past 10 years, and I feel incredibly grateful to be surrounded by such innovative writers who push each other and are also incredibly supportive of each other.

Talk about your backyard theater.

After seven years, we have officially retired from our annual backyard theater event, which was an all-day beer drinking, hot-dog eating, avant garde theater ritual that hosted space men, talking birds and dance numbers while the audience got drenched in sweat or by rain. One day we might bring it back out in the wild. There is a NY state campground that has an outdoor amphitheater, and we thought it would be cool to have everyone stay in tents and then have the all-day theater event in the amphitheater.

What people in Brooklyn are having the strongest cultural influence on you right now?

Mac Wellman continues to influence both of us as writers and thinkers with the belief that one can create new institutions. He’s a real advocate for DIY, and so are we. Also, his students are making the best work, so he has a wide net of influence. Antje Oegel is a great literary agent. Her office is in Brooklyn and she also helps runs 53rd State Press. Her clients are provocative and continually push the boundary of what theater can be. Terence Degnan was the first poet that Sock Monkey published for our reboot. He has become a pillar of support and advocacy for the press. He recently hosted a reading and represented Sock Monkey at the 2014 AWP conference in Seattle. His poetry invigorates and inspires but also his passion for other poets and the broader literary community is impressive. We are huge fans of Ugly Duckling Presse; we covet their books, even pet them when they arrive. We strive for that level of beauty with Sock Monkey. The CATCH performance series, originally founded by Jenny Seastone-Stern and currently curated and hosted by Andrew Dinwiddie, Caleb Hammons, and Jeff Larson, is a monthly performance series bringing dance, theater, experiments of all kinds to venues, including the Indivisible Dog gallery/performance space in Cobble Hill. Open Source Gallery is not just a gallery for artists, founded by Monika Wuhrer and Gary Baldwin in 2008. They also offer “soup kitchens” in December and hold the Church of Monika on Sundays. These events are forums for discussing art and it manifestations in a casual setting. See more at: http://open-source-gallery.org/about/#sthash.vbYluoxD.dpuf They also host a summer camp where kids can build their own soapbox derbies.

Marina Galperina

Interview by Paul D’Agostino

Reserving her right to not reveal anything too juicy to us, creative and cultural conduit Marina Galperina, who might prefer power napping with her eyes open to sleeping in order to break and comment on all sorts of newsworthy items—Brooklyn-centric and otherwise—as Managing Editor of ANIMAL New York, tells us a thing or two about the borough’s cultural scenes. Or lack thereof. Look her up on Twitter, @mfortki. She’ll keep you tuned in.

How long have you been in Brooklyn? What first brought you here?

I’ve been in Brooklyn for two years. After six years in Manhattan, I had some crazy shit happen and got stuck back in LA for a few months, then I escaped and moved into art critic Paddy Johnson’s basement for a few months in Clinton Hill. Tod Seelie, a photographer whose work I’ve been following for many years, was looking for a roommate in the Bushwick/East Williamsburg area, and I’ve been happily living there ever since. It’s the people that drew me here, really.

What kinds of creative communities did you first get involved with in the borough? What were those scenes like at the time? How have they changed?

I don’t think are really any scenes anymore, if there ever were any. It’s more like event-catalyzed space-centric chain reactions of meetings. Artists do poetry readings, bands make films, journalists put on shows… We’re all jumping from gallery to bar to venue to basement and running into each other. TRANSFER gallery just celebrated its first birthday, and I’ve been incredibly happy meeting and loving digital artists from all over through them, and filming Anthony Antonellis getting a net art RFID chip implanted into his hand for ANIMAL, of course. Miles Pflanz, Jane Chardiet and Bob Bellerue have done noise and video events at Silent Barn and around. They’re incredible. Eventually, I end up running into everyone at Skyler David Insler’s Alaska Bar at the end of the night, and we scheme up something new. It’s a perpetual, productive sort of mingling—half love-fest, half pissing context. The good people are really driven and collaborative and aren’t interested in money, they just want to do good things. I mean, that’s why I’m here, always frantic, and not hitting a bong on a couch back in Cali.

How about your neighborhood? What kinds of transformations have you witnessed in your time there?

When 285 Kent got shut down, I felt like I graduated high school or something. Williamsburg is the new East Village. There’s aggressive gentrification in my own neighborhood too, but there’s no way for me to complain about it without being hypocritical about my own privilege. The biggest problem is the rent. It’s fucking vicious. God forbid you have to move out of your apartment or that creaking DIY treehouse-cubicle you call ‘lofted room.’ Two blocks down the street will cost you an arm and a leg, every month, forever. But what are you going to do? Sink your teeth into the places and people you love, hold on as long as you can, and make new things.

You’ve devoted a great deal of your time and energy to keeping tabs on all sorts of cultural curiosities. Can you think of a couple BK-relevant stories from recent years that were particularly juicy, controversial, revelatory, terrible?

Cheap Storage’s last “New Years Do Over Party” got shut down by the cops. The Love Supreme were finishing the last chord of their last song by the time the blue boys made it to the stage area. We thought the flashing lights were part of the set for a second. And I’m not telling you anything “juicy.” I plead the Fifth. Well, mostly.There was a moment two years ago when things first felt right for me. I was at Quito Ziegler’s queer night beach thing in Fort Tilden with 300 semi-naked people I did not know, and I couldn’t stop jumping from blanket to blanket, talking my face off, mostly. It might sound sentimental and embarrassing, but fuck you. It was all really sweet.

Any thoughts of the future of the borough’s creative circles? Anything on your own creative horizon you’d like to tell us about?

I can only see as far as May, when ANIMAL and Glad Tidings are booking a show at Brooklyn Night Bazaar. There’s also a four day noise and video art festival at Silent Barn. And Bunny Rogers’ dark and brilliant poetry book is coming out. “The future”? I hope everyone keeps collaborating with everyone else and making more work. I love it when my friends become successful. That might mean broke and exhausted, but busy and happy.

Jason Diamond, Literary Editor of Flavorwire

Diamond is the literary editor at Flavorwire and founder of Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and his work has been published everywhere from The Paris Review to the New York Times. His Instagram is full of pictures of his dog, Max, which might not exactly qualify as culture, but also might.

So you’re the literary editor of Flavorwire, what are some of the most important things going on in Brooklyn’s literary culture today?

I definitely notice that the literary establishment (or whatever you want to call it…) is less frightened about going deeper into Brooklyn. I’m constantly seeing huge names mixed with emerging writers at the Franklin Park Reading Series, and bookstores like Community and WORD have really worked so hard to get bigger name authors to cross over the bridge.

There’s always a lot of chatter about the Brooklyn lit scene, but what does it mean to you? (If anything.)

I think living and writing in Brooklyn is a wonderful thing, but New York has always played host to writers and creative types. I think Brooklyn being the part of NYC associated with literature is part of the evolution.

Would you say that Brooklyn has a cultural scene that is distinct from that of the rest of New York?

Absolutely, but it borders on parody in some cases. Things like that Times piece on the Brooklyn-brand house in Ditmas Park made me want to go pack up and go to Staten Island or something. But I’m still constantly meeting new artists all the time, reading new writers from here, hearing new bands, and complain frequently about having to go to work in Manhattan.

Who are some of the writers that you’re most excited about right now?

I always go overboard with this one, and I feel bad admitting it, but if I were to pick a top five, I don’t think any of them are Brooklyn residents. But then again, my excitement blows like the wind. I loved Helen Oyeyemi’s Boy, Snow, Bird, I’m really excited for Teju Cole’s forthcoming book, and Walter Kirn’s Blood Will Out is on my nightstand. As for Brooklyn writers, Adam Wilson’s new collection of short stories, What’s Important is Feeling, is a fantastic book. I’m also really excited to read Chelsea Hodson’s latest chapbook on Future Tense. I could seriously go on and on about this, but I’ll stop myself right there.

What are some of the defining cultural moments of your life? (Movies, books, TV shows, albums… certainly don’t need to be related to Brooklyn.)

That seems like such an easy question until somebody actually asks it. I think I was lucky that I had one of those high school teachers that realized that giving me a lot of reading suggestions would benefit me a good deal, and I think that early jump really turned me into the reader I am today. As for other stuff, I guess I’ll just rattle off a quick list: Fugazi, Michael Jordan, The X-Files, Stephen Malkmus, Television’s Marquee Moon, Ellen Willis, the 1994 New York Rangers, the Twin Peaks VHS box set, Bikini Kill, AOL chatrooms, and Bruce Springsteen smiling at me.

Where do you see Brooklyn headed in the coming years? Will it still be a home to writers and artists, despite the high cost of living and lack of available real estate?

I’d really like to say yes to this, but it’s so difficult to tell. I think since the publishing industry has such a presence in New York, writers will always be in and around here simply based off that. Will we always be in Brooklyn? I don’t know. Remember the East Village? That place used to be lousy with writers. New York went ahead and ruined that and plenty of other neighborhoods, and if things keep going they way they are, the artists will probably keep moving. Maybe it will be deeper and deeper into Brooklyn until there is a writers residency established on Coney Island, or maybe we will all go to Queens like a few friends have suggested. For me, I’d really love to stay living and working in Brooklyn for as long as I can.

Aaron Hillis

Owner, Video Free Brooklyn

There are several ways you might have heard Hillis’s name before: as a freelance film critic for publications like the Village Voice; as a filmmaker in his own right; as part of the DVD distribution company Benten Films, which released films by Azazel Jacobs and Joe Swanberg; as the founding programmer of DUMBO indie-theater reRun; and, most recently, as the owner of Video Free Brooklyn on Smith Street, one of the last remaining independent video stores in the borough.

Is there much culture to consume right now in Cobble Hill and the neighboring communities?

Cobble Hill and its nearby ‘hoods have evolved significantly in the 13 years I’ve lived in the area, and the values of gentrification are obviously a mixed bag. Culturally, the changes I notice most are defined by Smith Street’s landscape of restaurants, bars and boutique stores, and the personalities behind them tend to be tastemakers. I’ve had many inspiring, fascinating conversations with staff and customers in my local cheese shop (Stinky) and wine store (Smith & Vine) just as I do in my own shop. It feels like the SoHo of Brooklyn, which is cool other than the criminally exorbitant real-estate prices.

How do you feel about the film scene in Brooklyn right now?

Brooklyn’s film scene is hopping, there’s no doubt. Articles were even written out of Sundance this year about how an overwhelming crop of Brooklyn-centric films dotted the screening schedule, so just like that old adage about being able to throw a rock anywhere in Los Angeles and hit a screenwriter, you could do the same in Brooklyn and clock an indie filmmaker. It’s a shame there aren’t more independent theatrical venues that are programming some of this wonderful work, but thank goodness for institutions like BAMCinematek, Rooftop Films and UnionDocs.

What kind of cultural influence can a video store have? When I took over Video Free Brooklyn in 2012, I had some grandiose but unproven ideas about the cultural influence of a video store. We’re still planning on holding events, screenings and panels when the opportunities make sense, but I’d say what has been surprising and thrilling is how VFB has become a High Fidelity-esque hangout (minus the snobbery). Just today on Twitter, I was included in a thread between a critic and a customer who had overhead a conversation I had with one of my customers, music and film critic Stanley Crouch. Every day in “the office” is like an impromptu salon, with rich and impassioned conversations often launched by whatever Blu-ray or DVD we’ve got spinning at the time. It’s part of the reason more and more of my customers are canceling their Netflix accounts.

Another one of the last few video stores in Brooklyn, Photoplay in Greenpoint, just closed. Do you think there’s a point when the industry finally levels off? All the Blockbusters are finally gone.

It was sad to hear about Photoplay closing; I thought they had a great shop. The video-store industry is a dinosaur, there’s no denying that, and I doubt there’s going to be a new renaissance of indie rental stores rising from Blockbuster’s ashes any time soon. Video Free Brooklyn is a curated boutique that I frequently compare to the vinyl record resurgence, and ours might be a special case because of my background as a critic and programmer, as well as only employing people behind the counter who work in film professionally. Currently, my staff includes a producer, a production worker, two filmmakers, and a programmer who works for a distributor by day. While they’re all assets that help define and sustain our brand, I’m not sure that’s a model that can be necessarily copied without the experience and social network I’ve been lucky enough to have had.

Have you considered doing more programming work post-reRun? Are you still involved in distribution?

I’m not currently working in distribution, though I’ve started strategy and festival consulting on the side. I’m a board member and programmer for a gem of a festival in Wilmington, NC, called Cucalorus, where I’ve gone every November since they screened my doc feature Fish Kill Flea in 2007. I would definitely love to program in NYC again, but to really make it pop, it would have to be for a stellar venue that would be willing to support week-long runs in order to score reviews. New York Times critic Manohla Dargis recently wrote that there are too many films flooding theaters, but that’s only partially true. Rather, we just need more quality control on the wildly unbalanced ratio of terrific-to-shitty movies that get released. The reRun Theater taught me a ton in just two years, and I learned that a progressive-minded cinema willing to put in the publicity legwork could absolutely thrive economically and culturally on the strength of significant, well-reviewed films that otherwise have no distribution, which I see all year long at festivals like SXSW, Cannes and Toronto.

What people and institutions in Brooklyn are having a cultural influence on you right now?

The Brooklynites who influence me most are the ones fighting uphill, sometimes downright Sisyphean battles to both preserve and make waves in film culture. There are far too many filmmakers creating amazing, commercially suicidal work to mention all their names—also, some of them might kill me for praising them on that quality—and I especially appreciate those who wear multiple hats. Critic-programmers like Nick Pinkerton and Nic Rapold have both earned their places in cinema heaven, and I’ve always admired Larry Fessenden’s DUMBO-based production company Glass Eye Pix, which supports emerging filmmakers looking to push boundaries and make smarter, character-driven, non-schlocky genre movies. What I love most about the Brooklyn film community is that it’s a big ol’ love fest for the most part, and I’ve always felt supported by my friends and peers.

Max Cavanaugh, Caryn Coleman, John Woods

Programmers, Nitehawk

After opening in 2011, this Williamsburg movie theater quickly became the most exciting one in the borough, not just for its Alamo Drafthouse model of bringing booze and food to your seats but also for giving independent cinema and an excellent repertory program a home in North Brooklyn. We spoke to Coleman (Senior Film Programmer), Woods (Cinema Programming Director) and Cavanaugh (Cinema Manager/Programmer) about what they do.

What do you have to keep in mind when programming for a Brooklyn audience specifically?

Caryn Coleman: The audience in Brooklyn is quite diverse, which is something that works really well for us because, as programmers, we’re interested in screening a real range of films. That affords us the opportunity to program everything from children’s movies, music documentaries, artist films, and even porn films. But what’s really important to us is involving ourselves in and building upon the Brooklyn community because it contains so many talented filmmakers, musicians, artists, chefs, and breweries. This is reflected across nearly all our signature series programming as well as our now annual Shorts Festival.

How do you feel about the cultural scene in Williamsburg right now?

John Woods:I first came out here in the late 80s to go see hardcore shows at The Lizard’s Tail on S. 4th. It really was a different place back then but so was the whole borough of Brooklyn. After moving here in the 90s and opening up Reel Life Video on Bedford, working with the public here made it seem like it was constantly changing, sometimes month to month. People have spent a lot of time talking and writing about whether that’s good or bad for many years now, but if you’re willing to make the effort, there’s always new things happening culturally in this area to discover and be a part of. Despite the dramatic changes physically and the huge influx of new people, there’s still a strong creative element here of both new and long-time residents. In spite of the constant changes to your environment, it’s really about what you make of it.

What about the film scene specifically? It seems to have had some ups and downs in the last year or two.

Max Cavanaugh: I’ve worked in film/video in New York for over 10 years, and I’ve worked at Nitehawk for two. During my time, I’ve experienced a scene that’s very healthy and supportive. If Union Docs has a DCP they need to tech or a filmmaker needs to test a sound mix, we’re available to help and offer our facilities. The community of film programers is also very supportive as we help each other find prints, get talent contacts, and put the word out for rarely seen repertory. There’s also a thriving scene of filmmakers here and, since our biggest challenge at Nitehawk is to fit as much as we can on our three screens, one of the more successful ways we’ve been able to highlight the local scene has been our Shorts Festival. We’re looking forward to the festival this year being even more ambitious.

Which film/series are you most proud of having put on/put together?

Caryn Coleman: I am particularly proud of the Karen Black retrospective I programmed in the spring of 2013 and being able to honor such an incredible woman. This year I’m excited about the current year-long Naughties series on 1970s porn cinema and a surrealist program in the works for July. Also, I’m especially happy with the opportunity I have to experiment monthly with artists and artist films in Art Seen.

Max Cavanaugh: My first screening at Nitehawk was actually before I started working there: Street Trash with Roy Frumkes and Rocco Simonelli in person. It was a huge success with two Midnite sellouts! After that I was offed the job. More recently, I am most proud of The Deuce Film Series, a monthly film series excavating the fact and fantasy of old 42nd Street where dead movies are alive, my favorite of which was the Japanese 35mm screening of Tobe Hooper’s Eaten Alive.

John Woods: Space Is The Place in June 2013, which was a Midnite series with 2001: A Space Odyssey, Aliens, The Fifth Element and Total Recall. Just a good time all around on a hot summer night to get transported to another place; people really responded to it.

Which film/series didn’t connect with audiences as well as you would have hoped?

All: Well, our screening of Poltergeist III as part of a Chicago series didn’t get the love we quite thought that it should. So, if it’s not The Road Warrior, Godfather II, or Empire Strikes Back, tread carefully with sequels.

What are you working on now that audiences can look forward to?

Caryn Coleman: I’m working on an early 1970s British children’s film program called Cheeky Monkies that will screen in May, as well as an all-night horror screening on Halloween, A Nite to Dismember, and the second annual Nitehawk Short Film Festival in November. Max Cavanaugh: The Deuce series is ongoing every month and I’m always excited for the next event. This summer I’m working on a ILM film series highlighting the work of Industrial Light and Magic post Star Wars before CGI (i.e., the very short period where they perfected the art of practical visual effects). John Woods: A lot of event screenings for the Music Driven series, with some exciting guests along with more fun Midnite series: Just Say Yes in April, Ask Me About My Mother in May and Future Noir in June.

You might also like