Olivia Thirlby Just Wants To Be Happy

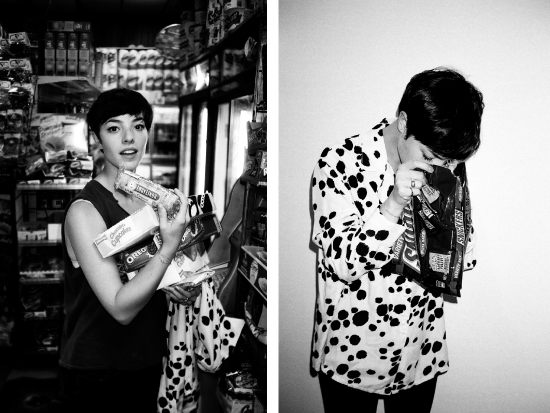

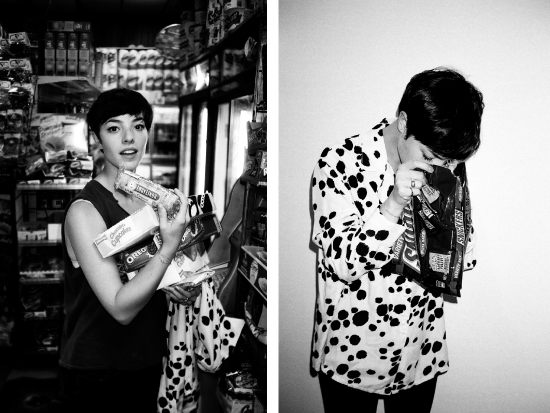

Many of Thirlby’s early roles, in indies with East Coast coordinates, languished—like her second film, Kenneth Lonergan’s post-9/11 panorama Margaret, released this fall after five years of recuts and legal disputes—but enough caught on that critics began to take notice. In 2008, Thirlby was profiled briefly in New York magazine, and confessed to her interviewer, “I wish I lived in Bushwick and was paying $650 a month for a crappy sublet.” She moved to a loft on Lorimer Street later that year. When she first moved there, having been “converted” by earlier adaptors, she appreciated “the fact that at one o’clock on a Saturday you could go eat brunch somewhere, and not have to wait in a line”; she has fond memories of Le Barricou, on Grand, and the since-shuttered Baba, on Lorimer (cross street either Ainslie or Powers, she always forgets the order after Devoe). She was happy, she says, to walk around the old neighborhood for this feature with her friend, the photographer iO Tillett Wright, which is another thing she liked about the neighborhood: “I was surrounded by a lot of really interesting people—some of whom I was lucky enough to actually meet.” (Even her Los Angeles friends are moving to Bushwick now.) And “geeky hipster” stuff, like having “the best tattoo artist in the world,” Scott Campbell, right around the corner.

Thirlby has several discreet tattoos on her upper arms, and a small ampersand above her right elbow, “my first tattoo in black ink,” which matches the tattoo of a close friend who “coerced me into making a commitment.” The ampersand, partly inspired by a line in the Magnetic Fields song “I Don’t Believe You,” symbolizes “placing emphasis on the forward-facing trajectory of time, and how each moment is followed by another moment that is potentially as potent, or is necessarily as potent, as the one preceding it.”

Thirlby took the subway to work when she was living in Williamsburg and shooting Bored to Death, which she found to be “a really lovely overlap” between New York City life (which involves not infrequent film shoots in one’s neighborhood, at that) and dream life. Bored to Death, lighthearted as it is, means something to Brooklynites unaccustomed to seeing their immediate environs (Hey, that coffee shop is Smooch! Hey, that’s a La Strada song on the soundtrack!) represented accurately in the mass media, which Thirlby appreciates, though she reserves her proprietary hometown pride for neighborhoods themselves: “I have a very good amount of native snobiness; I like to preach about how much the East Village has changed. And Williamsburg too, but I guess I can’t… but even then, in 2008, Bedford Avenue was still very much like Williamsburg.”

Being a lifelong New Yorker is also why she left: “Everyone must have the opportunity or create the opportunity to live somewhere other than where they’ve grown up. There’s sometimes an overwhelming familiarity here that is almost unpleasant, just because every place I might go evokes some memory of a former life there.” She misses her family and friends, though she appreciates the mobility afforded by her job, and Los Angeles, where “we’re in a little bubble which consists of your own house and your own car and your own pace,” nicely complements NYC, “once you get over hating LA so much.”

You might also like