What Happened to All the Music Blogs? Wild Honey Pie Embraces a New Model

The first time I see Eric Weiner, the man behind the odd music-video-website-cum-branded-content-agency The Wild Honey Pie, he’s emerging from a darkened doorway at the Central Park Zoo dressed in blue jeans, flannel, and plastic fangs: a sort of vampire cowboy. He’s grinning, both to show off the fangs and because he’s more or less perpetually grinning. A solidly built 27-year-old with jet-black hair and the relentlessly chipper air of a young marketing executive, he bounces between the dozen or so people milling around the far edge of the zoo in various stages of cowboy getup: denim shorts, red handkerchiefs, and the occasional plastic hat or Lone Ranger mask. As he sidles up to each knot of two or three people, he cracks a joke, compliments their outfits, and offers everyone a piece of candy.

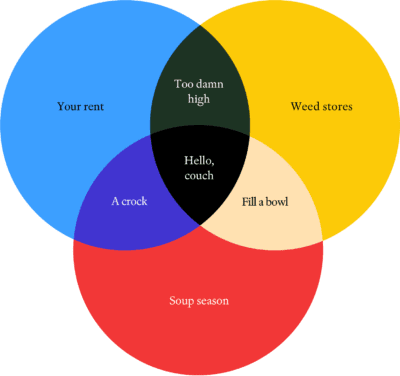

Everyone was there (and dressed up) for something Weiner had named “Spooky Mansion,” and for which he was more or less solely responsible. Most simply, it was three concerts by three bands held in an Upper East Side mansion (the zoo was the staging area where we met before being led there), each with its own spooky-ish theme. One was organized around The Shining and featured an eerily white room with a single bloody baseball bat leaning in the corner. The one I attended, by the art-dance band Rubblebucket, had a relatively less frightening cowboy theme. These performances were in turn taped and then posted on The Wild Honey Pie as a series of music videos, loosely organized into the coherent show: “The Spooky Mansion.” On another level, it was an opportunity to lock people in a room and advertise at them.

That day’s shoot, like every shoot the website produces–its series “On The Mountain” takes place in a ski lodge, and another, called “Welcome Campers,” happens at a summer camp–had been entirely paid for in advance by a host of sponsors, who in turn have their products both in the videos and available on-site, for free to the concert’s attendees. The site features no ads except the occasional “brought to you by Squarespace” stamped on a page between music videos and whimsical illustrations of sailboats. Since it has no ads, The Wild Honey Pie does not explicitly need to worry about the thing with which most online publications are obsessed: traffic. Ad rates are set largely by traffic (along with other metrics like social shares and the demographic makeup of the audience), and therefore largely determine the value of most online publications. Not at The Wild Honey Pie, though, where Weiner’s pitch to his sponsors–which, in addition to Squarespace, include Baked By Melissa (bite-sized cupcakes), Chameleon Coldbrew (coffee), and Newcastle (beer)–revolves around everything but the size of his audience, which he admits is small (internal figures estimate roughly 60,000 uniques a month; the site is too small to be tracked by large web audience data organizations). In exchange for freedom from traffic worries, has Weiner made his music blog into an advertising agency?

That publications of all shapes and sizes have had trouble adapting to the rise of the Internet is not, at this point, news. Only this year, The New York Times launched the NYT Opinion app at a party, with attendees including Lorne Michaels and Michael Bloomberg, as part of a major play to market its opinion writers beyond the newspaper and its site, putting them in the pockets (and nearer to the pocketbooks) of their readers. The app was shuttered four months later with little fanfare. Not long after, the Times eliminated 100 jobs.

Problems like these are not unique to the Times and have been particularly acute for music media. The list of music publications that have either folded entirely or gone online-only in the past decade is long and storied: SPIN, Blender, Paste, Vibe, Venus, Urb (some, like Magnet and Relix, went out of business and were revived). Online, with a few notable exceptions, music coverage vacillates between celebrity gossip, slideshows, and endlessly recycled discussion of the same few (extremely popular) acts. The industry they chronicle is famously on the ropes, as well. There are various metrics–sales, total revenue (including merchandise, touring, and other money streams)–all of which are generally agreed to have been more than cut in half in the past 15 years. Sales, for instance, fell from $14.6 billion in 1999 to $6.3 billion in 2009, according to Forrester Research figures released by the Recording Industry Association of America. Surprises are still possible–Taylor Swift’s 1989 sold one million copies in a single week, making it the year’s first platinum record which wasn’t the soundtrack of a cartoon. On the other hand, crowning the year’s first record to pass a million copies in November is hardly an accomplishment to crow about.

This is somewhat ironic, as the widespread adoption of high speed Internet, the invention of YouTube, and the ability to easily stream or buy music online at first prompted an explosion of music content, both online and off. Music blogs in particular wielded an influence so pervasive that calling a band “blog rock” was a common write-off of a particular sound. The perception was that a band could have a song explode on the Internet on Monday, be booked on Saturday Night Live that Saturday, and be on the cover of a magazine a few weeks later, all likely without recording an actual album. Indeed, this was the trajectory of acts like Arcade Fire, Vampire Weekend, and Animal Collective, as well as smaller acts who became instantly famous for varying lengths of time: OK Go, the French dance-pop band Yelle, The Annuals, The Morning Benders, British Sea Power, and a thousand more.

“A lot of mediocre bands seemed important at the time because music bloggers were desperate to anoint the next Arcade Fire,” says Scott Lapatine, the founder of popular music blog Stereogum. “You’d see David Byrne and David Bowie at Clap Your Hands Say Yeah concerts and be fooled into thinking something special was transpiring.” Such was the frenzy for blogs in the midpoint of the last decade that Lapatine found himself invited to curate showcases at South by Southwest or DJ industry events, despite having no experience as a DJ or even a passing familiarity with SXSW. Blogs seemed to be the most vital music writing in the world.

Today, their influence is much diminished, though some sites, like Lapatine’s, or the behemoth of online music writing, Pitchfork (where, full disclosure, I am a contributor), retain sizable audiences. How did we get from there to here?

“The secret is, nobody knows what they’re doing online,” says Maura Johnston, one of the founding editors of music blog Idolator, and, later, the music editor of The Village Voice. This is especially clear in music blogging, where lone people working in their spare time built thriving sites with loyal followings, only to have them destroyed by well-organized companies supposedly skilled in business.

Many prominent music bloggers did not start with any particular goal in mind. Lapatine started sharing MP3s through LiveJournal in the late 1990s when his personal friends got too old to talk about new music with him. The founder of popular and long-lived music blog BrooklynVegan, who agreed to be interviewed on the condition that he be credited solely as “Dave,” wanted to write a website which literally discussed vegan food in Brooklyn, but began posting music on the site, eventually becoming one of independent music’s marquee publications. Johnston was working in a bizarre position helping Major League Baseball figure out how to use the huge amounts of Internet bandwidth it had bought in the early 00s before the opportunity came up to help Brian Raferty launch Idolator in 2006. They were loners, and to this day none of them feels like they were part of any kind of clique or scene, despite all working in the same field at the same time, covering largely the same topics. When I ask Dave if he felt like he was part of a music blogging community, he replies, “Hard to say. Is there definitely one?”

The charismatic individuals with a strong point of view and a deep passion for their work who started many of the best music blogs combined the casual tone of voice and enthusiasm of a fan. What they were not, by and large, were business people, or even people who’d planned on becoming professional bloggers (a category of work that didn’t exist when they began their blogs). By 2006, the high-water mark of music blogging, it was starting to seem like big business. Some bloggers began looking for ways to cash out, while others began to be approached with buyout offers.

For many of these sites, that meant dealing with one company: SpinMedia, formerly BuzzMedia, and BuzzNet, before that. Their properties now include Stereogum, Gorilla vs Bear, SPIN, PureVolume, Absolute Punk, and several others. The firm essentially bought every music publication that was popular in 2006, including Idolator, where Johnston worked at the time. She was distressed at how little they seemed to understand how to operate in an online space, describing them as “a flailing Internet company trying to gobble up every music site they could.”

SpinMedia, she said, almost immediately began trying to change the site, “trying to dictate the content of Idolator in a way that was very much in line with traditional music writing tropes, and music writing promotion ideas, even though they rarely work. Like the exclusive premiere type thing. [Jeff Leeds, whom SpinMedia put in charge of Idolator] was really into the idea of me doing interviews with people, and I was like, ‘Look, this is an one-woman operation, and I have to be posting. I don’t have time to go someplace, do an interview, transcribe that interview, and then make it make sense. You’re wasting time.’”

Some of these sites have changed little since being bought. Others, like Idolator, are almost unrecognizable, and the worse for it. SpinMedia did not return a request for comment for this article.

In an age where anyone can listen to any music they want, quickly and for free, what exactly is the role of music media? From one point of view, it’s curation and discovery: overwhelmed with a tidal wave of new music every day, a listener turns to a brand she trusts to tell her what’s worth actually checking out. According to Johnston, this was not the case. When I asked her what seemed to draw the most people to her site, she quickly jumped in.

“Not the music itself, I’ll tell you that. That was the funny thing, whenever we would do discovery posts, they would always get less traffic than anything else. They would be read by the right people.

I mean, [Merge Records co-founder] Mac McCaughan has told me that the reason Wye Oak is on Merge is he heard them on Idolator. But influence doesn’t pay the bills.”

What does work? According to Johnston, the most popular pieces online were often tenuously related to music. “It was more about… trolling,” she says. “The 15 Worst Indie Bands, that was huge,” slightly mangling the name of a post by former Village Voice Media music director Ben Westhoff infamous among music writers, “The 20 Worst Hipster Bands.” It took potshots at a strange grouping of indie acts, including Death Cab For Cutie and Beach House, of whom writer Linda Leseman wrote, “Beach House lead singer Victoria Legrand has been compared to Nico, which makes sense in that Nico has an extremely vapid voice.” Published in 2012, it currently has 24,000 Facebook shares and is the highest-ever trafficked post on LA Weekly’s website.

“There were a lot of posts that were like, ‘Let’s point and make fun of particularly female music fans,’” says Johnston. “Looking at fandoms that might have seemed outré to your typical white male fan, 18 to 35, who’s straight. Things that might seem weird or worthy of mocking.”

In the absence of a clear mission, in other words, many music sites are engaged in an endless and destructive cycle familiar to anyone who works in online publishing: Story A got a lot of traffic or social shares, so make a copy. Then copy that copy, on and on. Measurement is the enemy of creativity, and it would be hard to argue that knowing exactly which pieces people read online, and for exactly how long, has improved the quality of content on the Internet. It’s not exactly an unfamiliar place for journalism–William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer essentially sent the United States to war in the 1890s in order to sell newspapers, running stories with misleading or wholly fraudulent headlines like “Does Our Flag Shield Women?” which wouldn’t be out of place today on sites like Upworthy or The Huffington Post. The situation is no less depressing for being familiar.

Eric Weiner comes from a successful and competitive family. His cousin started MTV Films and got him an internship, and later a job, with MTV, which would serve as his introduction to the music business. His brother is an agent for professional athletes. Like other bloggers, the very beginnings of The Wild Honey Pie were without much direction. Not long after, however, his ambitions for it became much more grand.

“I wanted to create a platform that was friendly and cheerful to be able to share a certain type of music. Playful. And very welcoming,” he says. “A place where you could go and not have to be scratching your head when there were 10 musical references that you had no idea what they were. . . I wanted to be part of a community and create a community of my own.”

He began shooting videos almost as soon as he started the site. This lead to putting on live events. “Our first one was our first anniversary show. Lady lanb the Beekeeper played, ARMS played, Alberta Cross played. Who else played that one? Well, it’s irrelevant at this point,” he says, “but I remember thinking, ‘Wow this is really cool and it’s so much more dynamic than doing the blog.’ Everything from that point forward ended up being about how we can connect the fan and the artist in a more intimate way.”

The Wild Honey Pie does not have ads. Looked at another way, The Wild Honey Pie is one long, ongoing ad. The site’s videos feature an almost-imperceptible sponsorship logo at the start, and never again. Weiner more or less books exactly whom he wants to book for his video series, films where he wants to film, and fills out the crowd with fans of the site whom he personally selects. The roster of acts he’s featured–Death Vessel, Shakey Graves, Freelance Whales, Plus/Minus, We Are Scientists, Modern Rivals, Tennis–is basically inexplicable, except that it perfectly reflects the idiosyncratic tastes of a white guy from Long Island who graduated college in 2009.

When preparing to do a shoot, Weiner first sends proposals to sponsors he feels might be able to work with him. “We say, ‘Here’s the projects that we have this year, the events, the video series, the blog stuff that we can do. Let’s find a way to get your products in the hands of the right people, let’s find a way to connect you with the right people, but, ultimately, let’s come up with something that’s not just the event, that transcends that, and that’s the video series, the giveaways, the contests.’ It is about creating longtail,” he explains. Weiner’s vocabulary is full of these kinds of marketing buzzwords, and he has the sort of boardroom hipness that allows him to say and sound as if he means things like, “We’re honored to work with every partner we work with.” He speaks in rapturous terms of the Taco Bell’s Doritos Locos Taco, which he call “a big campaign. Smart.” When running down the list of sponsors he works with, he punches each name with genuine enthusiasm: “Squarespace! MailChimp! Baked by Melissa! Newcastle!” I have never heard a person say the name of a cupcake company with more excitement and wonder.

Isn’t there something improper about funding yourself in this way? To call the titular mansion in your Spooky Mansion series “Squarespace Mansion,” after your primary sponsor? To build scenes around bars because one of your sponsors has a focus on bartenders? Does it not blur the line between content and advertising in a way that should make everyone involved feel uncomfortable? Weiner acknowledges the point but doesn’t feel he’s crossed any lines.

“It’s about creating a model and a business,” he says, “so that you’re not compromising your integrity by having brands involved. And you do that by selecting the right brands and having ultimate creative freedom to do what you want.”

My day at Spooky Mansion was chaotic and filled with delays. At one point, I was given someone else’s hat and kerchief and told to sit on a particular stool for a few minutes, only to accidentally spend the next hour working as an unpaid extra in what was essentially a Newcastle ad. I spent five hours on site but heard only one Rubblebucket song. The crowd’s enthusiasm waned, as everyone very quickly discovered how many tiny cupcakes they were capable of eating while milling around waiting for something to happen.

During the wait, I spoke with Melissa Presti, a 29-year-old Brooklynite and fan of the site. What had brought her there, I wondered.

“I did ‘On The Mountain’ earlier this year, in January,” she said. “I loved it. Eric welcomes everyone who’s been to one event to come back and enjoy the others. I just follow the blog and kind of went there by myself. It was like four full days. It was fun—a lot of people went solo to that trip. It was adventurous; there were six bands and I knew, like, half of them.” As the day dragged on, and I eventually had to leave, Presti was still there, making small talk, drinking free beer, and making new friends.

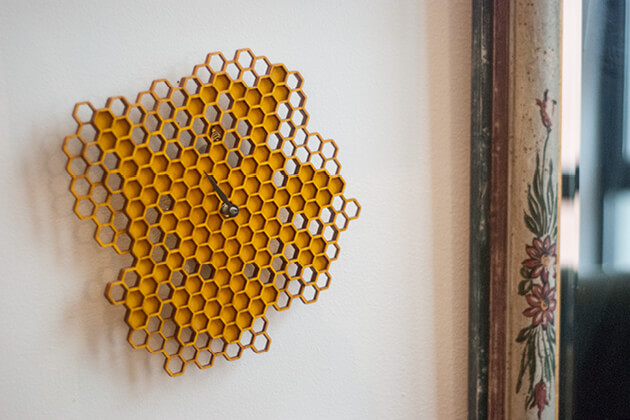

Photographs by Jane Bruce

You might also like